One astute reader of

a previous post observed that

although I seemed to imply that only

bitmaps

can be digital images, there also exists such a thing as

vector graphics

which are also considered

digital images. At the time, it was not clear in context what was meant in

describing an image as digital. While I conflated digital images with bitmaps,

which is inaccurate, I was only discussing bitmaps in that post, and the

conclusions therein are still valid.

Nevertheless, that reader raised a few interesting and related points.

What does it mean for an image to be digital?

What does it mean for a digital image to contain digital data? What does it mean for a digital image to contain non-digital (continuous) data?

Why do we not care about applying our techniques to non-digital images?

I would like to address the second point, which may be a point of confusion. In answering it, I hope the answer to the first and third points will become more readily apparent.

Bitmaps and Digital Data

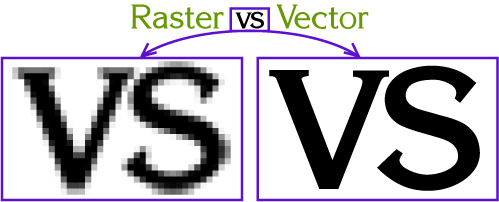

As discussed in the previous post, bitmaps (also known

as raster images) are a kind of digital image. Actually when people discuss

digital images they are almost always referring to bitmaps. This is in no

small part due to the ready availability of bitmaps in the form of digital

photographs, Adobe Photoshop, and even Microsoft Paint, all of which contain and

operate on bitmaps. The vast majority of digital images are bitmaps.

However, there is more to calling bitmaps digital images than just the

commonality of bitmaps. The bitmap actually contains digital data in the form

of pixels, which are element-wise approximations of a greater whole. In the

majority case of a digital photograph, the digital photograph is approximating

the real, continuous image seen by a digital camera when the picture was taken.

To elaborate on that point, consider the case of film photography vs.

digital photography — how much information is stored in each image?

Ken Rockwell explains on his excellent website

that the “resolution” of film is anywhere between about 87 megapixels to almost 2000!

As most digital cameras these days take images with around 15 megapixels, that

means film is still technically between 6 to several hundred times more data-

dense than digital. Does that mean that digital images actually convey less

information? Yes and no. Yes, they technically don’t have as much data, but at

the same time, both formats present a perfectly acceptable presentation of the

original scene. The takeaway is — a set of digital data are approximating

a nearly infinitely large set of data using a small, finite sampling of the

original set; and that the digital data represents the camera’s “own subjective

reality” of the image it saw.

Vector Graphics

When explaining bitmaps, I referenced

pointillism, the art of creating a

picture from many small points, and how these points approximate a larger, whole

picture. For painters (and likewise for drawers), the points are only painted to

facilitate the greater painting. However, if they so chose, they could simply

paint shapes. In fact, painting shapes is the classical art form when it comes

to painting, and pointillism is an alternate form.

Although obtaining digital images in the form of bitmaps is easy due to digital

photography, there is another way to obtain a digital image (digital here

meaning able to be stored on a computer). Much like painters can paint shapes of

color and texture, digital graphic artists can also generate shapes of color and

texture.

The technique for doing this is a little bit involved, but it revolves around

the idea of Bézier curves.

Put simply,

Bézier curves are special, mathematically defined lines which can be coaxed into

any shape, have any length, and be placed in any position in space. (The name

vector comes from the mathematical notion of vector being a line in space with

specific endpoints.) This makes them very powerful for forming shapes —

essentially a circle is just a singe curve, a square four curves, etc. Even

letters can be so represented!

The advantage to approaching digital images as a series of mathematically-

defined geometric shapes is related to resizing the image. Because the shapes

are described mathematically, their “size” is arbitrary. A circle can be small or

large, a line can be any width, etc. This is ideal for distributing graphics on

the Internet, because viewers’ screens can be any size. The scalability of the

size of vector images means that the image can be perfectly clear and the right

size in all situations. This is not so with bitmaps, where either multiple

copies of the same graphic are used at various sizes, or one extremely large

image is used everywhere. (This is in addition to the storage advantages from

storing a constant set of mathematical equations which work at all sizes.)

Why Do We Only Process Bitmaps?

If you’ve followed everything so far, the answers to the questions raised

previously should be falling into place. A digital image is, generally speaking,

an image stored digitally on a computer; however, it more often refers to

bitmaps, which is a digital image containing digital data.

Furthermore, we only speak about processing bitmaps because bitmaps

represent something greater than the sum of their pixels,

while vectors are

nothing more than the sum of their equations. A digital photograph is trying to capture an

entire scene of infinite details with only a finite set of information!

Processing that digital photograph can reveal hidden details, enhance

aesthetics, and more. Simply put, there is more to the photograph than just the

pixels.

On the other hand, vectors are generated by artists in a vacuum. There are no

hidden details or sub-optimal aesthetics which can be improved by analyzing the

properties of the image. The generated image is exactly the sum of its parts.

There is nothing more or less than what was put their by its artist.

That’s not to say that techniques which work on bitmaps won’t work on vectors

— in fact, they would most likely be easier to apply. There just isn’t any

point. Unlike bitmaps, where the image is a finite, lossy approximation of what

once was, a “secondary source”, a vector is an infinite representation of the

present, a “primary source”. Advanced algorithms are needed to coax more details

out of a bitmap, or to try and modify it without damaging the original image,

because it is difficult to modify the secondary source without losing the

information it has from its primary source. On the other hand, anyone can simply

open up a vector image and begin modifying it, because they have the primary

source.

Conclusion

In one sense, bitmaps are much more crude than vectors, because they’re a

limited copy. Yet there’s also many more possibilities — a vector image

needs to be generated in order to convey information, while a bitmap

intrinsically has information. In fact, detailed digital images such as digital

photographs can have many fine details which can be incredibly hard to recreate

using vector images. Although bitmaps may only have so many pixels, each pixel

is its own sandbox.