I recently began to use Emacs

as my default text editor for most things, having switched from

Sublime Text. Specifically, I’m using

the brilliant Spacemacs

project, which can best be described as a fairly comprehensive set of

sensible defaults and plugins for Emacs with a clever plugin architecture.

I used to be a casual VIM

user for remote file editing and a Sublime Text

user for local editing (with plugins). However, neither of these solutions

truly satisfied me. VIM is tricky to get fully working plugins for,

and a new set of plugins is needed for every target host. Keeping the

VIM plugins in sync is a chore even if effort is dedicated to it.

Sublime is also very nice, and has a better plugins story, but some of

the capabilities don’t seem to go far enough in my opinion. After hearing

many good things about Emacs using Spacemacs, I decided to check it out.

The Emacs Philosophy

Emacs is not terribly different in editing philosophy than VIM, although the way

it goes about that editing is somewhat different. Essentially, every time a

file gets opened, Emacs creates a “buffer” in its parlance as a cached

representation of the contents of the file. Once done,

the file can be saved and the contents of the buffer get flushed back to disk.

This is analogous to how most modern word processors function

(e.g. Microsoft Word). It’s also fairly similar to “basic” text editors

like VIM and Nano, which also

have the fairly basic functionality of opening/editing/saving down a file.

Where Emacs gets interesting and differs from other editors is its approach

to extensibility. Although VIM has a scripting layer which adds extra

capabilities to the basic VIM runtime, there are three primary limitations to

doing so (as I understand it):

- VIM uses its own language for scripting, called “vimscript”. Although it’s

not terrible, it’s not a “real” programming language, and it’s definitely

not as powerful as Emacs’ own scripting language, which is a “real”

programming language.

- Unlike Emacs, VIM does not encourage (although does not strictly limit)

using buffers in “creative” ways. Emacs plugins essentially use buffers as

portals to extra functionality, which makes them more like apps

(in the smartphone sense) than the name “plugins” would imply. As indicated

by the rampant success of apps in the smartphone space, having local

dedicated portals of functionality is a game-changer to any utility.

- Unlike Emacs, VIM does not have a very flexible internal architecture, which

limits how much functionality can be easily layered above the core editor.

I want to explore each of these in turn, because together they make Emacs a real

game changer.

Emacs Embeds Lisp

Those who have been programming for a while will know that the

“Lisp”

family of programming languages is considered “the little engine that could”

of programming languages. (For those unfamiliar with it, Lisp is the progenitor

of languages like Python, Ruby, and JavaScript, but is yet more powerful

than even those more modern languages.) Emacs is (in)famous for being (in many

senses) less of a text editor than a Lisp program which edits text, because

Emacs not only embeds Lisp as its scripting language, but

treats editing text as a program to be extended. Everything within the Emacs

environment can be extended or redefined, which enables things like…

Evil Mode: The VIM Emulation Layer

Emacs has a VIM emulation layer known as “Evil Mode” which

behaves flawlessly. Emacs is able to run a VIM emulation layer so flawlessly

because it is so extensible; because even basic operations like navigation

and word deletion/insertion are programmatic routines within Emacs,

and Emacs defines all its operations within Lisp, Emacs permits users to change

even its core functionality to behave like that of a completely different

editor!

Emacs Buffers Are Like Apps

Although I said above that Emacs’s default use case is to use buffers for

editing text, their use is limited only be a programmers’ ingenuity.

There are several world-class plugins that have been emulated on hosts

of other platforms because of how desirable they are:

Org Mode: The Organizer App

Org mode is somewhat famous amongst programmers for how

powerful and extensive

it is in allowing someone whose primary program is Emacs to organize their

life. It has many capabilities of a personal organizer, like a:

- Tea timer (I use this a lot)

- Calendar

- Task manager

- Wiki generator

I was using the port of Org Mode for Sublime Text when I was using Sublime Text,

but why use a copy when you can use the real thing?

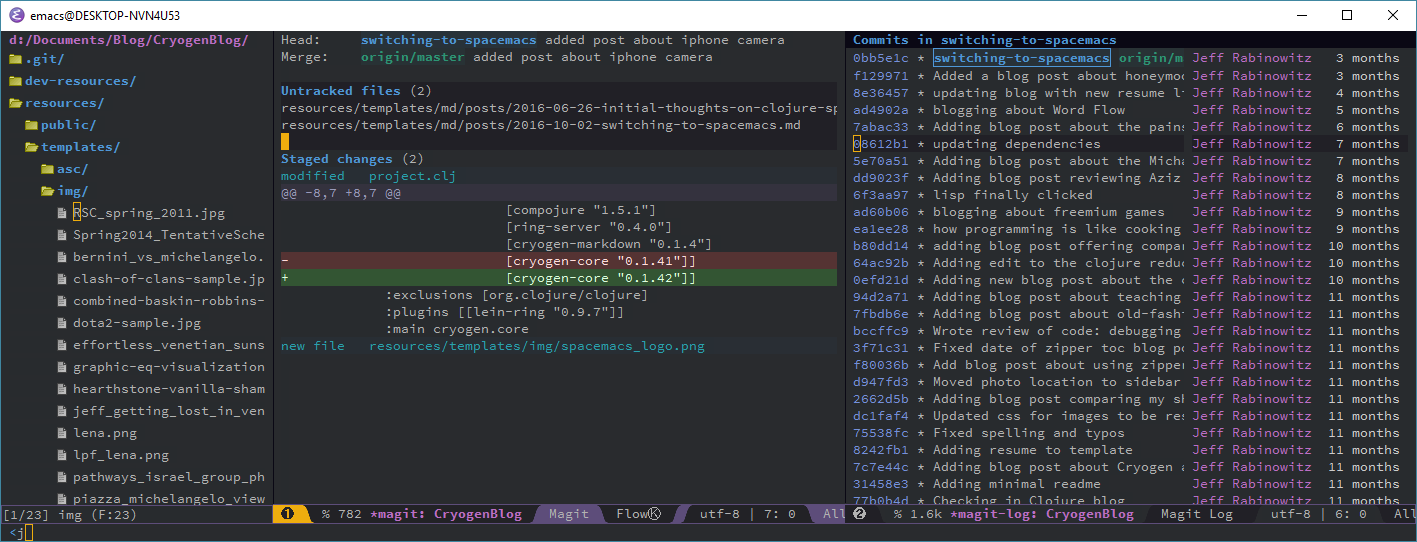

Magit: The Magic Git “Porcelain”

Magit is another typical example of powerful app (plugin) for Emacs. The version

control system Git is incredibly powerful

and fairly ubiquitous today among programmers, but is a bit unfriendly to use

without some high-level tools. Magit is one such tool - it wraps the low-level

plumbing of how to operate Git in several friendly(ish) subcommands

(essentially like screens in an app) to expose most of Git’s power without

inducing hair-ripping or screaming. Here again a plugin leverages Emacs’ buffers

as a host system for embedding essentially a stand-alone app capability.

Helm: Like Siri for Emacs

A capability most programmers enjoy from their IDE’s is the ability to

“jump to anything” - to name some snippet of a word in a file

looked at weeks ago and to have that file pulled up and that exact word found.

Emacs can be extended to have this functionality added with a meta-framework

known as Helm.

Helm describes itself as a “incremental completion and narrowing selection”

framework, which is basically a way of saying “smart autocomplete and prediction”.

Pretty much every plugin within Emacs leverages a secondary plugin wiring into

Helm, which not only enables traditional searches, but also allows Helm to

search across the application functionality added by those plugins!

A couple of the neater examples I’ve seen are Helm allowing me to search

recent files, recent buffers, recent commands, searching for commands I didn’t

know existed, and telling me information about those things as well. I like to

think of Helm as Siri but for Emacs.

Helm is made possible because Emacs has an architecture with many intermediate

levels of scaffolding, from which apps and plugins can extend. So not only can

plugins provide “app” functionality like Magit and Org Mode, but they can also

provide “meta-framework” capability, like adding a Siri-esque capability.

Bonus: TRAMP Mode

As many programmers have experienced, sometimes it’s necessary to drop onto

a remote server and started poking at configuration files and seeing what’s up.

A frequent frustration is that these servers don’t have my configuration files

to make Emacs work the way I like it. Although I could potentially copy my

configuration to that server (pending the IT security policy), it gets tedious

to keep those configurations up-to-date and present on every server. If only

there was a way to edit those files using my base Emacs profile…

But there is! TRAMP for Emacs

is a built-in utility which allows editing remote files as if they were local.

This means that, while editing those files, every existing plugin for Emacs

(the aforementioned Magit, Helm, etc.) work as if the file was local!

No more copying the configuration everywhere – instead, copy the files

locally under-the-hood.

Final Thoughts

Although it’s only been a couple of weeks, I like what I see, and will

try to update this post later with any further thoughts. I’ve been using

Emacs mostly for editing shell scripts, markdown files, XML files, and of course,

for access to Helm/Magit/Org Mode/TRAMP. However, I’m sure I’ll find more uses

for it shortly, and when I do, I’ll try and blog about them.

Helpful Videos

I found the following videos indispensable in teaching me about Emacs/Spacemacs

and helping me understand its philosophies and capabilities:

- Spacemacs ABC: This is a helpful

series which basically goes in alphabetical order through the various plugins

and utilities integrated by Spacemacs. I found it useful both for familiarizing

myself with the Spacemacs environment and for learning some of the more

nuanced modes/commands/apps (Magit).

- Emacs for Writers:

Despite the name sounding somewhat snarky (as if writers couldn’t use Emacs!),

it’s actually a sincere anecdotal recollection by and of a technical writer

who vastly increased his productivity (and programming chops!) by doing his

writing in Emacs instead of Word. I didn’t learn a ton from this, but still

found it enjoyable.

- Emacs as a Python IDE:

Although PyCharm is still my favorite

Python IDE, I was impressed to see how capable Emacs can be when properly

customized with the right plugins. I’d say this is better than Sublime,

if not quite as good as Visual Studio or PyCharm.

- Overview of Org Mode:

Although Org Mode is very deep and one can spend weeks learning it, there’s a

few concepts which are helpful to learn up front, and this video covers them.

- Rewrite Git History with Magit:

This one is good for covering the basics of Magit.

- Magit Advanced Capabilities:

Despite the name of the video, this is basically a showcase of some of the more

powerful capabilities of Magit. I highly recommend watching this after the

previous video.