For the past few years, I’ve been interested in a more powerful digital photography

workflow solution than the brutish practice of shuffling JPG files around on my

hard drive and hoping for the best. I have really been seeking one (or more)

specialized programs which can handle the common photography tasks of organizing

photos from the moment they leave the camera to their final resting place on my

hard drive (and/or backup server), and performing common photo editing upon them

like curve adjustments and blemish removal. These solutions also needed to work

natively on Windows, integrate well with NAS solutions, and be capable enough

with RAW files. I was willing to pay for the software, but I didn’t want to have

to spend more than $75, and certainly not over $100, considering I am at best an

amateur photographer. I’m also mindful of my privacy.

After spending several hours researching the options available

to me, I have decided to use ACDSee Pro 10 as my one-stop shop.

Organizing vs Processing

There are two fundamentally distinct, but intricately related digital photography tasks:

image organization and photo processing.

Photo organization is the task

of organizing photos on a computer, whilst

photo processing is the task

of editing photos on a computer. (If this sounds familiar to you,

click here to skip to my analysis.)

Photo Organization

Organization, quite simply, is the task of filing all photographs onto one or

more computers with the goal of benig able to easily find, edit, and view those

photographs later. Generally speaking, more powerful photo organizers offer

greater flexibility and more useful ways of grouping, finding, and batch-editing

photographs. (The most powerful of these organizers essentially lend themselves

to a workflow called culling, which is the task of selecting photographs worthy

of keeping from a large photo shoot, and eliminating the rest.) Common, powerful

ways of organizing photos include face tagging and facial recognition, date tagging,

album making, and adding searchable keywords or tags. All of these different

organization styles require compiling a database of sorts within which to place

photo references and associated metadata (such as those faces, keywords, tags, and albums).

(It’s important to note that simply clumping files into folders on disk is not the

same as building a formal database system with a powerful way to interact with

many photos. Albums don’t exist without having ways of associating multiple

photos into a single unifying concept; one photo should be able to appear in

multiple albums without having multiple copies of that photograph on disk; the

unifying data which names those photo files (wherever they are) constitutes a

database.)

Photo Processing

Photo processing involves potentially destructive changes to digital photograph files

to alter their appearance in aesthetically pleasing ways. This runs the gamut

from minor geometric tweaks to altering the perspective and colors of a photo

to remove optical distortion and optical illusions. To enumerate some informal

tiers of photo processing capabilities:

- The most basic photo editing options, some of which are included with operating

system file browsers, include rotating photos, and sometimes cropping. Red

eye removal is basic and not included within file browsers but is essentially

taken for granted in even the most basic editors these days.

- More advanced editing capabilities which are often associated with

Adobe PhotoShop (but in reality are available in most photography oriented

image processors) include adjustments to white balance, level and color curves,

exposure and saturation, noise reduction, and sharpness adjustment. These

edits will often apply to the image as a whole, and change the parameters of

the image across the board, with some level of intelligence.

Although not strictly a holistic adjustment, editors in this tier usually

include at least a basic form of cloning and healing, which are used for tasks

like removing pimples from portraits and photos of people.

- More robust editors often include tools for controlling vignetting, chromatic

aberration, lens distortion, and sometimes even perspective changing and

liquification. These are powerful techniques for holistically changing how

specific local combinations of pixels appear within a digital image, and tend

to require more finesse than merely e.g. tweaking colors across the board.

- Very powerful editors like Adobe PhotoShop offer (in addition to the formentioned

clone and heal tools) local image editing, which allows an editor to select

portions of an image within which to apply edits exclusive to other portions.

This is commonly used for “face swapping”and selective sharpening

or lighting/saturation adjustments.

- Most decent editors support non-destructive editing,

wherein a file can be edited multiple times over hours, days, or weeks, without

requiring multiple destructive operations. The original file is preserved

as such, and the history of edits to that photo are serialized to either a

dedicated container file format, or else stored within a database, so that

the original photo is always available for further (similarly non-destructive)

tweaks.

- This isn’t even really a type of editing, so much as a different class of it.

Many powerful cameras can shoot what is called RAW,

wherein the camera faithfully records everything it saw when the photograph

was taken, with no compression or loss of detail. Although this level of detail

allows for edits that otherwise would be impossible (because far more granular

data is preserved in RAW than in other common formats like JPG), special software

is required for RAW processing. Each camera has a slightly

different way of storing what it saw, and RAW processing software either needs

to be made for/by a specific camera manufacturer to process that camera family’s

own RAW format; or else a third party must provide RAW processing for many

different RAW formats. A common reason to shoot photographs in the RAW format

is to recover dynamic range for an image with mixed lighting.

Typical Photo Database Types

Not every photo editor has a database (consider PhotoShop and Microsoft Paint),

but the best ones generally do. I’ve learned that the common database types are

one of fundamentally two distinct types:

- Indexes are databases which store references to files on computers, and

remember fast ways of finding them by tags, keywords, faces, dates, albums, etc.

The database here consists of the records of photo locations and metadata,

but the photos live outside of the database, and can be processed externally.

The index database is also often called a catalog.

- Some databases actually store within themselves all the user’s photographs.

This often allows for a more seamless editing experience for beginners or

simpler users, because the files

can be conceptually replaced with photographs with no loss of generality, and

photo editing photographs within the same database is simpler.

In this case, the photographs get copied into the internals of the database,

increasing the database size.

Programs Under Consideration

For my purposes, I really want the ability to have a pleasant viewing experience

of my photos from my program. I also want the ability to do fast lookups by date,

location, and person, and to create photo albums. As far as editing is concerned,

I would prefer the ability to do the common image editing tasks like lighting

and exposure adjustments, even on RAW files. Facial recognition is a big boon,

but I am willing to live without it, because of the sacrifices to privacy it

often entails.

Apple Photos

My most recent experience with a do-it-all program has been Apple Photos,

Apple’s newest iteration on photo management (it’s the fusion of the now end-of-life

iPhoto and Aperture programs). I’ve tinkered with it on my wife’s laptop a couple

of times, and overall, I think there’s a lot to like:

- It comes “free” with the operating system (so no marginal cost)

- It has both offline facial recognition and a tag system

- Freeform album creation, photo timeline, location map, and “smart” albums

- A reasonably complete set of photo editing techniques for a free editor, and

it even has rudimentary RAW support

However, there’s two primary strikes against it for me as well:

- Photos stores all of its photos in an opaque “database” folder inside a specific

user’s home directory. Although this has advantages (no micromanaging folder

layouts or locations, no duplicate photos, etc.), it comes with a disadvantage:

the database is essentially limited to the size of the available file system

of the underlying computer. The database can be placed on an external drive,

but then the program is essentially useless without a network connection to that drive.

Having a single, atomic database container limits this application squarely to

users who don’t mind storing their entire photo library on a single computer

- Obviously, Photos is only available for macOS; I use Windows, so this isn’t

really useful for me as a daily driver.

Google Picasa

The venerable Picasa program has a lot to like. It has many of the same capabilities

as Apple Photos above (although its offline facial recognition is more rudimentary

than Apple’s and especially Google’s most recent offerings). However, as it is

end-of-life, I’d rather not invest in beginning to use the program now. I’m also

uncertain of how advanced it can be for certain advanced photography workflows

(notwithstanding its free price). Picasa uses an index database over the file

system, but it’s not recommended to run it against network-stored photos. (Some

users also find that the database becomes unstable when moved between computers.)

Adobe Lightroom

One of the most widely acknowledged photography workflow programs out there is

Adobe Lightroom.

Lightroom sits in an interesting place – it is mostly a non-destructive

photo editor with an emphasis at batch processing of many photos at a time; and

it also has good indexing options like keywords and facial recognition through

its catalog (indexed database). The catalog here stores both the non-destructive

edit history of the imported photos, as well as their locations.

Whenever photos need to be removed from the catalog (will discuss below), they are

exported from the system.

However, some power users complain that the program can become sluggish when working with very

large sets of files, and so endorse exporting photos from the Lightroom catalog

when they are no longer needed in the spot. It sounds from this that Lightroom

is not really meant for long-term photo organization, although it can hold up

fine on large projects one-at-a-time.

That being said, Adobe has some of the best RAW processing and intelligent photo

processing algorithms in the business; Lightroom is considered the golden standard

for working and enthusiast photographers. If I was a working photographer, I would

probably shell out for Lightroom, but because I’m not, justifying the $150 for it

is a bit difficult for me. I took a hard pass, even though it’s a reasonable option.

Capture One Pro

I won’t mention more about Capture One

than to say that it’s considered better optimized and faster than Lightroom at

nearly everything Lightroom does. If Lightroom is for enthusiasts and professionals,

I assume Capture One is only for serious professionals. Not for me, but it looks nice.

PhotoShop Elements

In the opposite direction from Capture One is

Adobe PhotoShop Elements.

PhotoShop Elements (PSE for short) sits in an interesting place between PhotoShop

(just an editor) and Lightroom (30% organizer and 70% photo processor). It contains

the enthusiast features of PhotoShop itself (e.g. it’d never work for a serious

professional but it’s usually plenty for amateurs and enthusiasts) and has a

sidekick feature called the “organizer”. PhotoShop itself can do most of the requisite

photo processing that Lightroom can, although it’s less optimized for a photography

workflow and a little better at a generic graphic designer workflow. The Organizer

is neat in that it embeds a little database for common organization techniques,

including some of the facial recognition and timeline/mapping features from

competitors. As such, PSE is in a decent position for casual photographers

experimenting with portraiture or the like. However, don’t imagine that the organizer

works well with network drives, and its not-photographer-oriented workflow makes it

a weak choice considering it still costs $80.

ACDSee Pro

An almost unheard of program I found after serious sleuthing on the

Digital Photography Review forums

is ACDSee Pro.

It can be seen as either a more robust and lightweight alternative to Lightroom,

or as a more photography-centric (and lightweight) competitor to PSE.

It has a similar concept as Lightroom in that it can easily import photos into its

catalog (index) for processing and tagging (no facial recognition though).

And it has a fully-fleshed-out photography workflow with both non-destructive RAW

processing and JPG editing. Its sticker price is $100, which is a little

high considering that it’s gunning against the well-known PhotoShop Elements

which is “only” $80. However, it’s on sale this week for $50, which I consider to

be a fantastic price for what it offers.

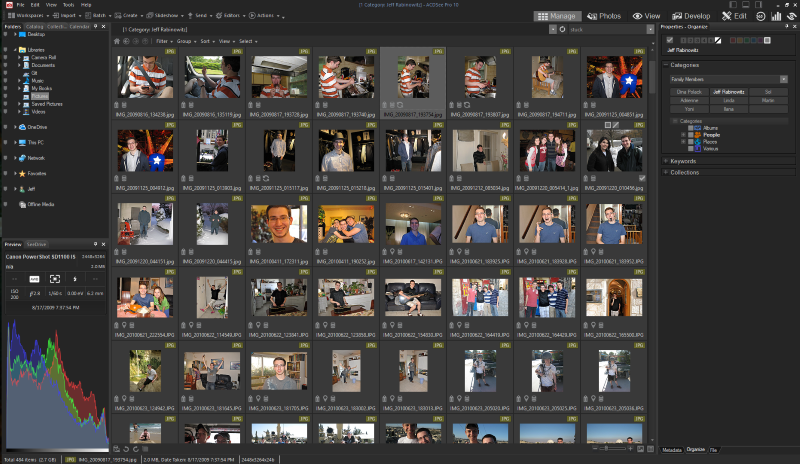

Manage Mode

The “Manage” workflow of the app is an intelligent, photo-centric file browser.

Although this may not sound so powerful at first blush, the ability to combine

a local index of tags and categories with typical file browsing and a global file

cache ends up being far more fluid than it sounds at first blush.

The ACDSee Manage mode is incredibly fluid for deft maneuvers around the photo catalogue.

This mode is almost completely analogous to Adobe Bridge

in its file-browser centrality. However, Bridge is (especially) meant to be a

graphic designer’s workhorse for punting files between programs like InDesign,

Premier, Illustrator, in addition to PhotoShop. As a dedicated program, ACDSee Pro

is more specialized for photography workflows because it is a single program.

(There’s a stripped down version of “ACDSee Pro” titled “ACDSee”, which is much

closer to Bridge in that it does not have powerful editing built in.)

ACDSee has another similarity to Bridge – all assets which have been examined

in the program are transparently and automatically indexed; but a user can batch import

entire drives into the database through a setup/settings option. This feature allows

one to set up all initial photos and have any subsequently taken ones get imported

on-the-fly. (A potential hiccup is that if photos are moved around outside of the

program, the existing references become orphaned and data can be lost.)

A workflow I very much like from ACDSee (which I assume Bridge and Lightroom also have)

is the ability to work with photos quickly from the moment a camera is plugged in

until the photos are ready for “shipping” to the internet or a printer. My workflow

looks like:

- Plug in the camera and import from it

- Filter by date and select desired photos to import

- Copy them to a staging folder. Add desired photos to the “image basket” (shopping cart)

and move them to a working folder. The staging photos which are no

longer desirable can be kept or purged.

- Do any editing upon the photos in the working folder and then copy them to a

destination/output folder.

- Optionally, upload the photos to Flicker/FaceBook/SmugMug/Zenfolio or copy

to a network drive.

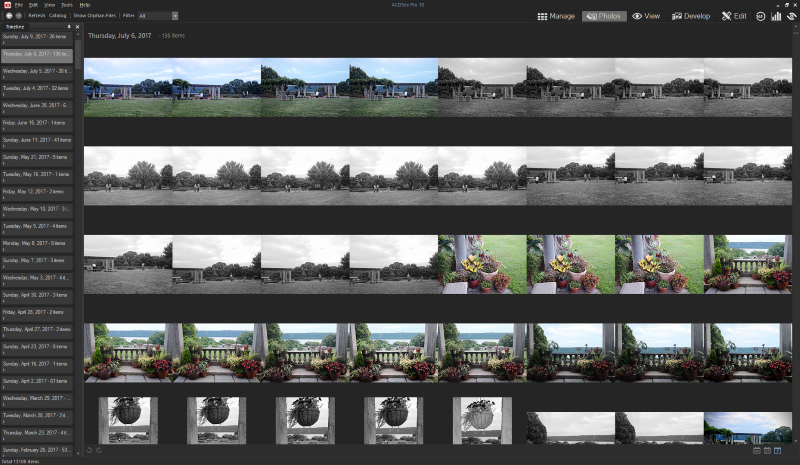

Photo Mode

Like most other organizer/editors, it supports a primitive timeline and map view

(although its map view is more limited than most of the competition), not shown.

I’m not really sure what to say about this timeline viewing mode, otherwise. It’s

hard to jump from it into other modes in a “powerful” way, other than right clicking

on a single photo at a time. I think it’s nice to have but isn’t nearly as powerful

as the other modes.

Although I find the Photo mode visually attractive, it’s not really meant for productivity work.

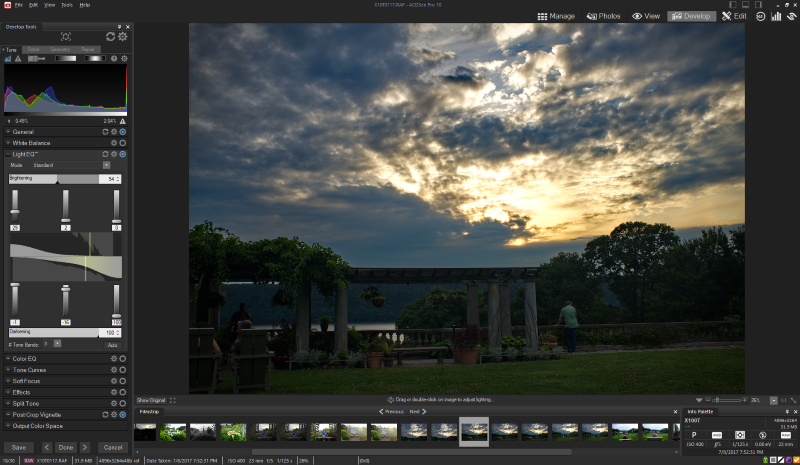

Develop and Edit Modes

These should be self-explanatory to anyone who has ever used Lightroom, but I’ll

go over this nonetheless. “Develop” mode is (especially but not exclusively) for

image-wide tweaks to properties like white balance, saturation, etc., in other

words, holistic tweaks. Develop mode is of particular interest for developers

shooting in RAW because most (all?) of the tweaks in Develop mode can be done

to RAW files without having to leave the RAW image (which sacrifices some level

of image detail by definition).

Develop mode is useful for 85% of photo processing a typical photographer does, in this case boosting dynamic range.

For most photos, I maybe want to do some cropping and noise reduction, followed

by tweaking some colors and exposure and lighting; Develop mode is ideal for this.

I especially like the Light EQ mode, which has intelligent sliders for continuously

adjusting between the original photo and more dynamic versions of it.

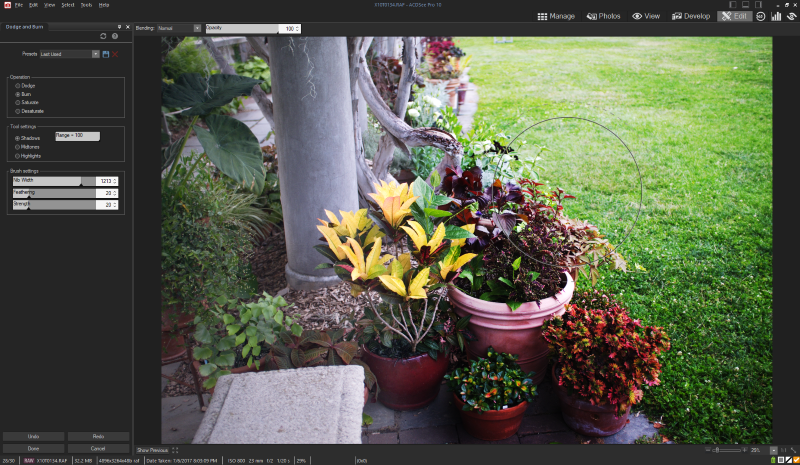

I’ve poked at Edit mode, which is useful for local editing (the “Ultimate” version

of the program also has layers but those aren’t so useful to photographers).

For good photography, it shouldn’t be necessary to lean heavily upon local editing

of photos for every single photo. That being said, local edits are a good way of

making the image “pop”, using techniques such as

dodging and burning.

Using the burn tool in Edit mode in ACDSee Pro.

Why I Chose ACDSee Pro

The photo editing provides non-destructive RAW editing and a very intelligent set

of lighting and level sliders. Furthermore, there’s included a basic facility for

local image editing for sharpness, saturation, etc. I was very impressed with how

much I was able to get done so quickly, without really having to mess around learning

special features or leaving my workflow. I can easily dive into some photos, even

RAW photos, play around a bit, save and return later, and when done, export everything

to a web album or photo scrapbook or the like. And it even works with my network server!

Although I only had a few days to play with it, I was so impressed with its combination

of features at its great price point that I was willing to commit to it long-term.

Its index database works well for my networked photography use case, is incredibly

quick and responsive to use, and results in good looking photos in record time for me.