This summer, I finally pulled the trigger and picked up a Nintendo Switch, so

that I could play “Breath of the Wild”. (A friend was kind enough to lend me his

copy so that I didn’t need to pay $60 out of pocket.) I know I’m well over a year

late to the game, but I still wanted to briefly share my thoughts.

TL;DR skip to the conclusion already!

Warning: Very minor spoilers below, unless you skip the conclusion.

Breath of the Wild’s world is breathtaking and expansive.

Zelda meets Skyrim

When “Skyrim” came out in 2011, it became both my first and favorite game open world game

(narrowly tied by “Assassin’s Creed II” thereafter). While I’ve since played a few titles

which tried to reclaim the throne (“Shadow of Mordor”, “Dishonored”, and many of the

“Assassin’s Creed” sequels), I strongly feel that “Breath of the Wild” is the true heir

to the open-world game throne.

Open world exploration

In my opinion, “Breath of the Wild” manages to achieve two impressive feats in

one swoop: it manages to both feel as epic as “Ocarina of Time” in terms of the

overworld size and variety, and have as rich a world of characters and environs as

“Majora’s Mask” (a game which, need I remind you, is primarily side quest).

“Ocarina of Time” was notable when it was released for managing to achieve an

impressive overworld size, which (through clever map design) never felt like

you were entering a linear “instance” when entering a sub-zone (like Kakariko Village).

Although “Majora’s Mask”, “Twilight Princess”, and “Skyward Sword” technically all

had overworlds which were just as large (if not larger), none of them felt like

they reinvented the path “Ocarina” had already trailblazed. “Breath of the Wild”

is a major evolution for the series, as its overworld spans every zone in the game

(other than the shrine-based puzzle instances, and the medium-sized quest dungeons).

Taking major cues from titles like “Skyrim” and “Assassin’s Creed”, Link has no

real limit to how he can navigate the map to pursue his quest; brute force combat

is generally discouraged in favor of clever combat setups.

A brilliant innovation of BotW is how Link can use his glider to soar through the air.

“Breath of the Wild”’s revolutionary contribution to the genre is its “gliding” mechanic.

The glider Link gains through the prologue is not simply another way to explore the

world, but rather an integral part of engaging with some of the most fascinating enemies

the game has to offer.

The glider is used not only for crossing rivers or dropping onto unsuspecting enemies;

drawing a bow mid-flight slows time and enables Link to fire a volley of arrows.

Lest you think this is overpowered, it’s all moderated by Link’s new, upgradeable stamina bar;

if you enjoy airborne antics, you may want to focus on giving Link stamina upgrades and potions.

Another refreshing primary story-mechanic change of “Breath of the Wild” is that

the “main” dungeons are actually completely optional. For the brave/suicidal, one

can actually glitch out of the prologue region and attempt to charge Ganon’s castle;

without any weapons, armor, magic, or health potions, one is unlikely to get within

a mile of the castle, let alone survive an encounter with Ganon; but it’s great that

the game finally takes a step back and eliminates all linearity from the game.

Dungeon sizing

A major consequence of pulling most of the game’s content into the overworld is

that side-quests for hearts and dungeons shrank correspondingly. Dungeons and puzzles

were affected differently.

Some Zelda fans may feel that “Breath of the Wild”’s dungeons are anemic, with all

of the meat of the game pushed into the overworld. It’s certainly true that the

puzzle difficulty of the dungeons has been significantly reduced.

However, I’m actually of the opinion that the game plays better for having more

manageably-sized dungeons. I found many of the dungeons of previous titles to be arduous affairs,

requiring quite a bit of stamina and free time for a player to successfully tackle.

(I hope I’m not the only person who regularly dreaded a new Zelda game’s “water” dungeon.)

Dungeons

A refreshing story-mechanic change of “Breath of the Wild” is that

the “main” dungeons are actually completely optional. For the brave/suicidal, one

can actually glitch out of the prologue region and attempt to charge Ganon’s castle;

without any weapons, armor, magic, or health potions, one is unlikely to get within

a mile of the castle, let alone survive an encounter with Ganon; but it’s great that

the game finally takes a step back and eliminates all linearity from the game.

Puzzle shrines

In many previous Zelda titles, heart containers would be scattered across boss

dungeons, regional hub side quests, and in grottos off of the overworld. While

completionists would be tempted to accumulate as many of these as possible, the

hidden nature of many of these containers, especially when situated inside dungeons

with artificial time limits, would discourage casual players (like me) from

grabbing more than the bare minimum necessary to have a sane chance at fighting

bosses.

This was exacerbated by how there were no notable benefits of picking up a heart,

other than simply having it. Once a player knew that there was an area containing

a heart, they could skip it safe in the knowledge that nothing else important

was in that area, and that no benefit would accrue from trying to solve the related

puzzle.

Some puzzle shrines are readily located in the overworld, while others require completing a quest before they reveal themselves.

“Breath of the Wild” cleverly kills two birds with one stone here to fix the

previously somewhat lacking puzzle mechanic:

- The majority of such puzzles are located within a shrine; one knows that the

inside of the shrine is a self-contained area of no import to the main quest.

- Once a shrine is “activated” by visiting it, Link can later teleport back there

at any time for any reason. No matter how remote the shrine or how hard the puzzle,

a player is never punished for deferring it until later.

There’s a couple of other nice tweaks, which are the cherry on top of this:

- Link’s reward for a shrine is a kind of currency which can be exchanged for

either a heart container or a stamina container.

(There’s a character in the game who can exchange heart and stamina containers.)

- Not all shrines entail puzzles. Some simply have a combat trial.

- Some shrines (like the one depicted above) require solving an overworld puzzle

instead of a puzzle within the shrine. I solved most of these overworld puzzles,

and I found them refreshing.

Combat

Another arena in which I think “Breath of the Wild” synthesized genre favorite

mechanisms with conventions from prior titles is its combat system. In my mind,

it mostly draws from “Skyrim” in terms of the weapons, armor, and pre-fight strategizing,

and from “Wind Waker” in terms of mid-combat mechanics (especially the quick-time mechanic).

I think it also takes nods from “Assassin’s Creed”, and has some of its own unique

contributions.

Like “Assassin’s Creed” especially, many of the open-world encounters are more

manageable by thinning crowds one-by-one or leveraging an environmental “trap” to

defeat entire groups in a fell swoop. This fits in well with the imperative to

explore a way around a fight, as there’s often a powder keg or boulder conveniently

laying about if you take a tour around an area.

Once within a fight, though, the combat tends to feel very much like a typical

Zelda title. Enemies rarely “take a swing” at Link at the exact same moment

and rarely draw so close as to completely box him in

(unlike “Assassin’s Creed II”, where I too-often found myself surrounded by 3-4

high-level fencers). And they don’t have to - no matter when in

the game, if you charge a battery of fire-archers, more than one moblin,

or a lynel with his buddies,

you’ll probably have to reload your last save.

This rainy mountaintop fight with a Lynel is representative of both the graphics and combat.

A mechanic I enjoyed from “Wind Waker” is back and improved - the “dodge-quick-play-attack” mechanic

(formerly a “parry attack”) can be triggered not only with a dodge, but also with a weapon

attack (parry) and a shield block. Some of these are harder to execute than others

(I think I pulled off a shield block maybe twice), but the reward is always sweet;

Link completely negates the damage (or reflects it) and then gets a quick-time event

to deliver some (damage amplified?) swings.

Boss fights

There’s technically only five true bosses in the game - one for each of the dungeons,

plus Ganon himself. I actually found their difficulty level on-point; doable when

poorly equipped if your skill level is high enough, but not a joke with poor

skills even if over-equipped. I did the dungeons counter-clockwise from the Zora

area (i.e. Zora, Goron, Rito, Gerudo), and thought that difficulty was quite

manageable.

For some reason the Rito and Zora zones seem to be the same combat

difficulty, even though the Zora area is the “recommended” starting dungeon;

as a result, I found the Rito area to be a bit of a joke after finishing the Goron

area; but it’s nice that there’s two “easy” dungeons, one “medium” dungeon (Goron)

and one “hard” dungeon (Gerudo).

Ganon himself is about as hard as the hardest (Gerudo) boss fight. As you might

have guessed, when in the final phase of the first form, he is invulnerable until

you get a parry attack against him. However, I (accidentally) discovered that if

you have a certain magic ability, you can actually stun Ganon out of his

invulnerability. I found this quite helpful because I’m mediocre at quick time events.

It’s a nice nod to casuals like myself that Ganon can be beaten even without flawless

skills, if you get far enough into the game.

Graphics

“Breath of the Wild” has a generally positive graphics setup, with minor hiccups

which I didn’t find limiting. As with most games on the Switch, the resolution

in handheld mode is much lower than in docked mode. To my eyes, I didn’t notice much of a

framerate difference between the two modes, whether in “simpler” areas or “harder”

ones.

Continuing the brilliant legacy of “Wind Waker” on the Nintendo GameCube, Zelda

chooses to favor the cel-shading

graphics technique. While widely panned in 2003 as a cop-out by Nintendo for not

trying to compete toe-to-toe with Microsoft and Sony on raw graphics performance,

cel shading emerged as a prescient choice of graphics technology. For any given

dollar of hardware graphical performance, the admittedly cartoonish cel-shading

is more fluid than the corresponding “realistic” graphical rendering. As an added

benefit, the “cartoon” look ages much more gracefully than the “realistic” look;

a decade on, “realistic” graphics become “blocky”, whereas “cartoon” graphics

look like a stylish and artsy choice.

Inside dungeons and shrines, the graphics generally hold up quite well. (There’s

often quite a bit of atmospheric and environmental “stuff” going on in the dungeons,

which benefits from being a separate instance than the overworld.) Meandering

about the overworld, there’s usually not much amiss in terms of graphical performance;

the draw distances were always impressive and lived up to expectations.

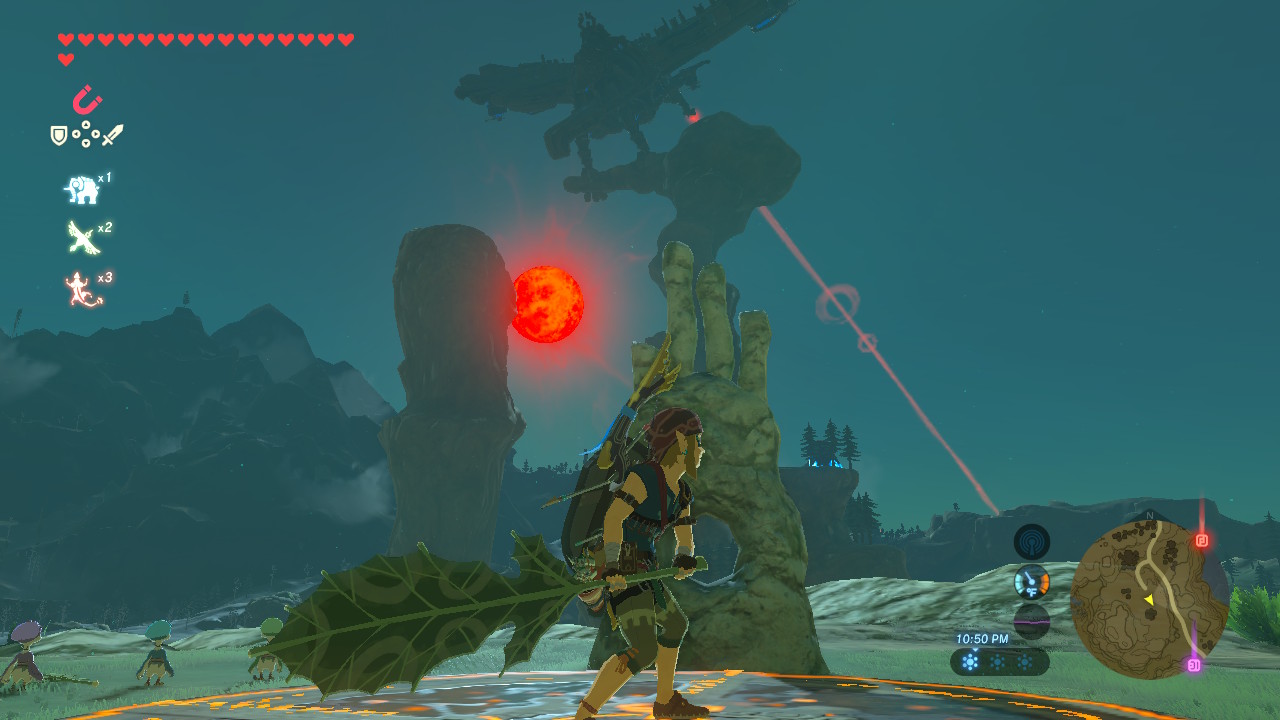

It’s only when a lot is happening at the same time, such as fighting an army of enemies

in the rain, or right before a blood moon, that things can get a bit rough.

This rising blood moon means I’m probably going to have to fight more enemies in ten seconds.

Overall, though, I’d say that the rare choppy moments rarely detracted from what’s

otherwise a jaw-dropping tour-de-force of breathtaking vistas and vivid, animated

creatures.

Story and characters

I mentioned above that I think that “Breath of the Wild”

shares many of the best elements of “Majora’s Mask”. One place where that’s quite notable is how

quirky and eccentric many of the side characters are, and how funny their side quests can be.

The motley cast of quirky and eccentric side characters helps the side-quests hold interest into the lategame.

“Majora’s Mask” was notable as the first (3-D, if not ever) Zelda title where simply

completing the primary quest would in no way sufficiently equip a casual player

for the final boss encounter; Ocarina before it all the crucial “side-quests”

folded into the primary quest, “Wind Waker”, “Twilight Princess” and “Skyward Sword” afterwards

too had bland, forgettable side characters (perhaps because the

companions in each were more developed).

BotW side quests are often of the less memorable “find/discover” and “fetch” genre,

but the characters themselves tend to be intriguing enough to make a player want

to see a quest through to completion. Players are rewarded for keeping in mind

the more interesting characters they encounter, as some faces can occur over and

over again.

“Memories”

This Zelda game has another story element borrowed from games like “Assassin’s Creed”;

across the map are a dozen anonymous locations where Link can trigger a “memory”

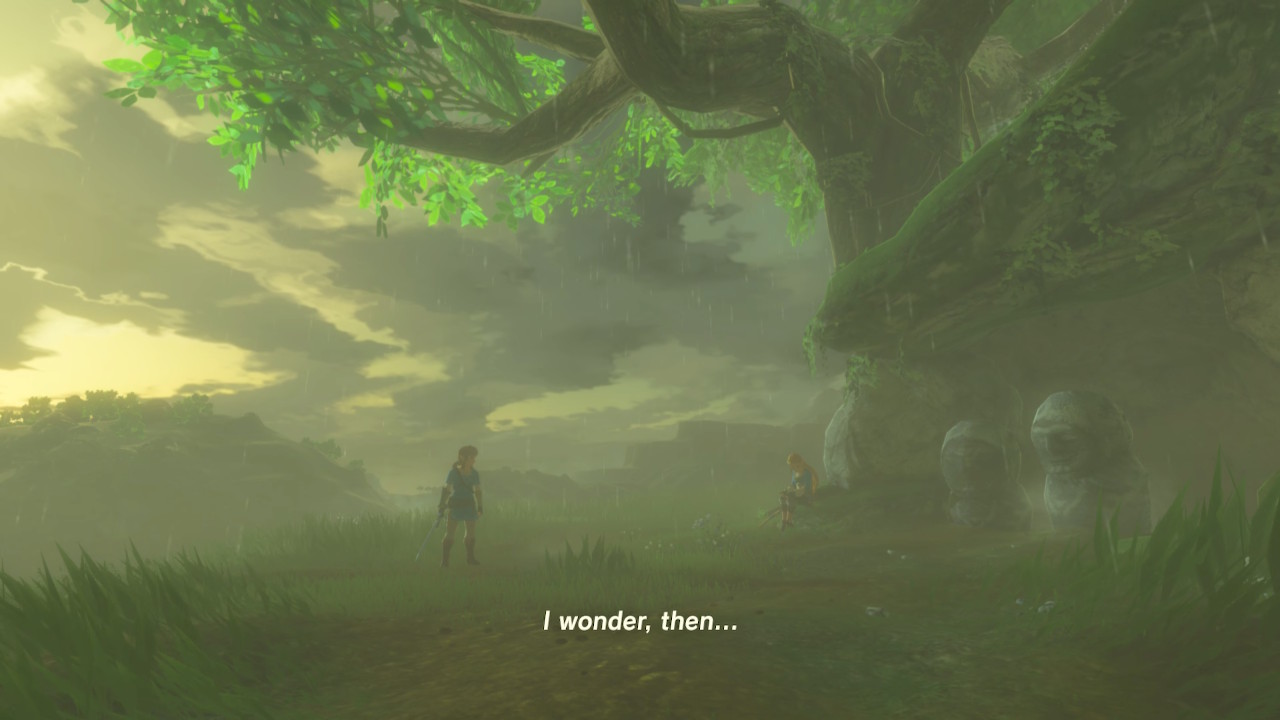

and corresponding cutscene of some forgotten bonding time with Zelda before

the calamity of the present day came to pass.

A memory which occurs not too far from the starting plateau.

These are completely optional, and you gain no useful items/abilities for unlocking all

the memories. That said, for story nerds (like myself), you may find it interesting

to gather up all the memories. I “cheated” and used a guide to find most of them;

I highly recommend this, as two-thirds of the memories are in the middle of nowhere

without any identifying landmarks.

Other mechanics

There’s quite a few other new gameplay mechanics Zelda introduces/borrows from other games

in the genre:

- Potion crafting

- Cooking

- Horseback riding

- Breakable weapons/bows/shields

- Upgradeable armor

- Warp spots (and quite a few of them)

- Environmental hazards (e.g. heat stroke, hypothermia, electrocution)

I was generally a fan of all of these mechanics; they resonated well with a large

and open world; shouldn’t such a world be hazardous to the unprepared?

One mechanic that I often heard griped about was the longevity (or lack thereof)

for the weapons in the game. Other than the Master Sword, every weapon in the game

can break, whether a strong one or a weak one, a club or a bow or a shield.

Many complained that they found this particular mechanic detracting from their experience,

as a good weapon won off a dungeon boss may be broken long before reaching another dungeon.

Compounding this frustration is that, while Link can upgrade his weapon inventory

via a gathering side quest, giving Link spare room to carry disposable, middling weapons

at the same time as his strongest ones, this side quest is possible to miss/skip

(unlike shrines, which are introduced and stressed early on in the prologue).

In my experience, I found that I had enough inventory to never worry about the weapon

breaking mechanic, but (and this is a huge) I “cheated” and looked up the quest

for growing my inventory. If I went in on my own, I actually definitely would have

missed the quest to grow my inventory, and been really unhappy. So I’m actually of

two minds here; I think that someone who goes in with eyes open will do fine, but

for someone who shuns guides, they may find themselves unintentionally on “hard” mode.

Takeaways

My first Zelda game was actually “Majora’s Mask”, not “Ocarina of Time”. We often

remember our “first” of something more fondly than successors, and I felt that

way about Zelda until now; for all its technical superiority, I was more

attracted to “Majora’s Mask”’s openness and rich, secret-laden realms than

“Ocarina”’s comprehensive overworld. While “Wind Waker” had much to like from

both of those titles, it didn’t feel as compelling as either (although it was still

quite good). And while “Twilight Princess” and “Skyward Sword” were both enjoyable,

worthy entries in the series, they can’t hold a candle to “Ocarina” and “Majora”.

With “Breath of the Wild”, I finally feel that Nintendo has out-done themselves.

You definitely don’t need me to tell you this (especially so late in the game),

but “Breath of the Wild” is a must-play for anyone with a Nintendo Switch. I

remember that for several years following the release of “Skyward Sword”, many

Zelda fans were nervous that Nintendo’s first stab at an open-world game with

Zelda would be a misstep and a disappointment.

“Taming wild horses? Climbing mountains? How can Nintendo pull this off – they’ve

never done this before!” the naysayers would murmur.

I’m so glad at what Nintendo lovingly crafted – “Breath of the Wild” is such a perfect marriage of the Zelda

charm with classic open-world mechanics that it will surely win a new generation of

fans, the same way I was won over by “Majora’s Mask”.

If you’ve been living under the same rock that I have been, you owe it to

yourself to check it out.